Larry Kovalevsky takes us back to Old Shanghai: White Russians, sailing on the Whangpu, and nothing at all on Pudong side...

- Stu Lloyd

- Aug 29, 2025

- 10 min read

The Kovalevskys were part of the 25,000 plus diaspora of displaced ‘White Russians’ who called Shanghai home. “My father was born in Kiev,” Illarion 'Larry' Kovalevsky tells me. “He came to the Far East from Vladivostok, where my grandfather was boss of the Customs House, because the White Russians were running away from the Revolution and the Reds pushed east. Russians who didn’t want to join them either had to jump into the Pacific Ocean or move to China.”

His parents met in Vladivostok, his mother’s family moving to Harbin, a Russian-designed showcase city in China which boomed on the back of the new 1917 Revolution and the Trans-Siberian Railway. Soon 100,000 Russians called it home. At the time it was the most fashionable city in China, with new season designs and trends showing up there before Shanghai and elsewhere. They married there, and moved to Shanghai around 1923 where Illarion was born -- the only child of his father’s first marriage -- in a French catholic hospital a couple of years later.

Larry knows his father was in the Russian Navy for some short time as an engineer. “But the first memories I have of him working were as a shift engineer at a large brewery, a Jardine Mathieson company,” part of an Oriental empire founded by the world’s most successful opium traders. He shows me a photo of Kovalevsky Senior shoveling coal in a suit and tie in Iwo Mills: “That was probably to show you were a European.”

But as White Russians they were on the lowest social rung, and stateless. “We had travel documents issued by the Chinese government but we had no nationality. No Chinese nationality or any other nationality for that matter. But that didn’t seem to worry anyone, it was a condition you accepted.”

Though barely old enough to comprehend what “stateless” meant, it did not escape his attention that other people celebrated National days: “British kids had their St George Day, American kids had their 4th of July, and you realize they had a bonding with whatever nationality, whereas we White Russians didn’t have a bonding to much except the Orthodox Church, and there were plenty of Orthodox Churches about.” Half the Russians were Orthodox, the other half Russian Jew, who tended to stick to themselves but had a big influence on the Russian community as they controlled all the foodstuffs and were also the big businessmen.

Indeed, the Russians did impose themselves on Shanghai, especially Avenue Joffre in the French Settlement which became ‘Little Moscow’, with congregations of Russians clamouring for blinis, herring, caviar in grocery shops. “I can still eat caviar by the bucketful if I can get hold of it.” Balalaika players held fort in cafes and doorways.

A balalaika hangs on a wall in the townhouse he and wife Thora call home in Sydney’s suburban northwest. (She is the product of a Norwegian master mariner and an Aussie mum.)

A small Australian flag hangs near the door. Larry fingers his map of old Shanghai, the pleasure capital, in its 1930s heyday. “If you superimpose it on the map of new Shanghai, it’s still the same, nothing’s changed. I mean Shanghai’s now 20 million people or something,” he says. The Bund and Nanking Road were “very busy, very crowded, very colourful” with its serried citizens jostling shoulder-to-shoulder along the pavement.

The art deco high rises on the neo-classical Bund (where the four-storey Shanghai Club held sway) left an impression, especially the distinct Cathay Hotel, a million-Pounds statement built by Baghdad Jew Sir Victor Sassoon, and viewed by many as the finest in the Far East: “Sort of a spire, that sort of outward construction,” Larry remembers. It attracted the likes of Noel Coward and Douglas Fairbanks. “There were a lot of hotels in Nanking Road, the main boulevard for Western matrons of society. And they had their favourite coffee shops and their favourite hotels.”

Most entertainment was done outside the home, at night. “It was a big treat if we were taken out to a hotel, sometimes to the Cathay but more often than not the Palace next door.” The ladies would put on their hats, the men their jackets and ties. The strains of jazz emanated from doorways, most famously the Peace Hotel where a group of players from the Wuhan Conservatory of Music would play daily for decades and come to define swinging Shanghai in the world’s mind.

The downside to this halcyon picture was beggars. “Everywhere, misshapen beggars with broken limbs crawling along the footpath.”

The Shanghai waterfront along the Whangpu River was also jammed. After all, the port was the fifth largest in the world by then. “All big ships, up to 27,000 tonnes, which were absolutely massive in those days. Everyone went everywhere by ship. There wasn’t much in terms of wharf accommodation, and ships were parked mid-stream one after another, anchored, tied to large floating buoys. The passengers and goods were transferred by lighter, then on to shore. Between the ships and the shore was absolutely chock-a-block full of junks, because the local trade was all done in junks. And they were very picturesque; most of them were old and decrepit. Sails falling off ‘em, but somehow they made progress up the river.”

Another ubiquitous feature was coolie labourers. “Always singing, had their poles with a couple of baskets on the end of it, and they always used to chant. In winter time they wore typical Chinese cotton stuff, and in summer they all wore linen trousers, a cap or a coolie hat.”

Then of course there’d be the attendant smells. “But you don’t notice it, you get used to it. Asia is Asia. You have the smells and you also have the cooking smells, which all form into one. One sort of smell of Asia,” says Larry who’s since ventured to Borneo, Manila, Hong Kong, and Thailand, the latter two where one of his sons worked for decades.

The river was a constant source of fascination for Illarion, who would regularly sail his little dinghy on the Whangpu. “On the east side of the river, which is now a separate city and in those days was Pudong, was mainly vegetable gardens and rice paddies.” He occasionally ventured over there with his father because that’s where the boat-builders were. “But there wasn’t much to see apart from paddy fields and market gardens. No substantial buildings, not there.” We pore over photo albums which back this up: behind him on the river it’s just barren mud flats. “If I went back I’d be catching the ferry to Pudong, and see the difference because apparently it’s a remarkable city,” he says.

In those days Shanghai only spread westward from the waterfront. “You went from the Bund, west to Bubbling Well Road, to Yu Yuen Road, and then you sort of ran out of the city.” It was here, at the western extreme, that Illarion used to wander off and play. “You could ride a bike there, feed the ducks in the pond. It always surprised me those ducks were never eaten: the Chinese normally will eat anything that moves! There were ice cream vendors: very, tasty chocolate-coated ice creams that I had a passion for.”

Their double-storey house sat on a small block of land. The neighbours were mainly Europeans but there were some Japanese, too; hardly surprising since the latter had outnumbered the British in Shanghai since 1930. They had a permanent servant called Vaskar, from Manchuria, who spoke good Russian. “He was the cook and also the boss of the servants. He brought his wife with him, she was doing some housework and bossing him about in Chinese which we didn’t understand. And we also had some other guy who did the garden. So we had three.” Sometimes Vaskar would put on Chinese fare – “traditional Chinese things with chopsticks and so on” -- other times a traditional Russian spread. But best of all from the servants he learned to swear in Chinese: “Servants delight in teaching young boys things that they shouldn’t teach them,” he roars.

Did their situation strike him as being privileged? “Undoubtedly you realized not everyone was in the same boat, but you took it for granted. I saw it as a permanent thing. The Euros lived well. Our family was members of the European Club, I think; it had a swimming pool.” Europeans were “a hell of a mixture” of Germans, English, some White Russians, Americans.

Shanghai was a well-renowned melting pot, with the Shanghai Municipal Council -- known as the British Concession -- actually a consortium of around 50 different national interests representing around 48,000 foreigners by 1932. The amount of foreign investment topped three billion dollars, the largest investment by outsiders of any city in the world. “But the Brits organised it, and the police force and general administration was English colonial style, wearing the khaki shorts, gun slung over one shoulder, and walloping stick in one hand because they used to wallop people,” he laughs. “The Sikh police were all big handsome guys with big moustaches and had their colourful turbans on. Distinct from the French concession, which was just south of us, and their police wore French pillbox caps, and had a lot of Animes, because they imported police from IndoChina, Vietnamese mainly.”

The streets where Illarion lived were sealed roads, nicely maintained, “all these servants wondering around with brooms sweeping the sidewalks.” Larry remembers the cars: “Chevvies, La Salle, Fords, and in the early 30s they came out with a V8 motor. Rolls Royces … of course the rich Chinese liked to have face.” Those not so fortunate scrambled onto trams that plied the French settlement, or trolley buses in the International Settlement, while rickshaws were ubiquitous.

**

In March 1935, it was back to swinging Shanghai for Illarion’s dad to work at the Auto Palace. In addition to General Motors vehicles, he was also now peddling Rileys, Crossleys and all sorts of obscure British marks. Among the GM marques were Chevrolets, Pontiacs, Buicks, Cadillacs, and La Salle “which was a cheap Cadillac.” (Interestingly, cars were priced and sold in American dollars, as were other items of substance like houses and ship travel.) “American businessmen lapped up La Salles and Cadillacs, that’s outward show. We’ve arrived! You do that in China because the Chinese do it themselves.”

By those standards, poor old Illarion had not arrived. On “sloshy wintry days” he’d be given twenty cents to catch a rickshaw to school, otherwise he’d walk about a quarter of an hour. By Shanghai standards it was a large school with several hundred students, run by the International Settlement Municipal Council. Larry remembers it as very British. “We had an Eton-type cap, on the cap badge were lots of miniature flags comprising the shape of the Y. And we stood up for the teachers when they came into the room, and we got walloped in the backside if we didn’t. The headmaster, a fellow named Bennett, walked around with a cane in his hand and he belted you very quickly if he saw something wrong,” he laughs.

Swashbuckling Bennett encouraged healthy pursuits. “Bigger boys were supposed to play rugger to make men of them. Younger kids like myself played soccer, cricket, and games we devised ourselves … we’d jump on each other’s backs and try dislodge someone else.” Marbles were also popular. “But mainly we tried to keep out of the reach of the headmaster’s stick! That was the smart thing to do.”

The 12-acre Shanghai Race Course (on Bubbling Well Road, named for an artesian well which supplied drinking water for the ritzier addresses in town) was the main sports arena, housing many soccer pitches. There were other spectator sports. “Jai Alai was imported from the Philippines. It’s like handball and they’ve got baskets on their arms, and they develop a hell of a lot of speed, propel it at a couple of hundred miles an hour. And that was paid entertainment, and the stars were all from the Philippines. There were a couple of courts there. I used to enjoy having a look at Jai Alai.”

The race course was also where Amy Johnson landed her tiny plane in 1930, part of her 191-day solo voyage from London to Australia. Illarion’s parents didn’t let that photo opportunity slip by.

Having returned only once in 2007 to Shanghai since that hasty departure in 1937, Larry felt “sort of in touch” with the city over the intervening seven decades. “From this small beginning, all rice and paddy fields,” he says poking the old map, “it’s grown to this thumping great city.” One of the first things he tried to do was locate the house they lived in. “I’ve given my son maps but he’s never been able to find the street. Yu Yuen Road appears on this map,” he says, pointing to a recent tourist map, “but they’ve got a railway going right through West End Gardens suburb.” Jiangsu Rd metro line station exits here today, with not one, but two Starbucks on the corner. Overall, everything had changed so much, Larry had no touchstones, and was a trifle disappointed by that.

Over a leisurely cup of tea, we pore over his father’s photo albums, old China documented by a Box Brownie. The outskirts of Shanghai reveals nothing but flat, empty spaces, with perhaps a couple of houses here and there. Warlords. “Some sort of rail disaster,” he says pointing to a pic where bridge spans had crushed carriages. More photos of mangled trucks and trains. Another of a train on its roof. “Another disaster of some sort … my father liked disasters!’ A sunken ship in the Whangpu. Nanking Road flooded, with hundreds of “yooloo yooloo” (sampan boats) afloat on it.

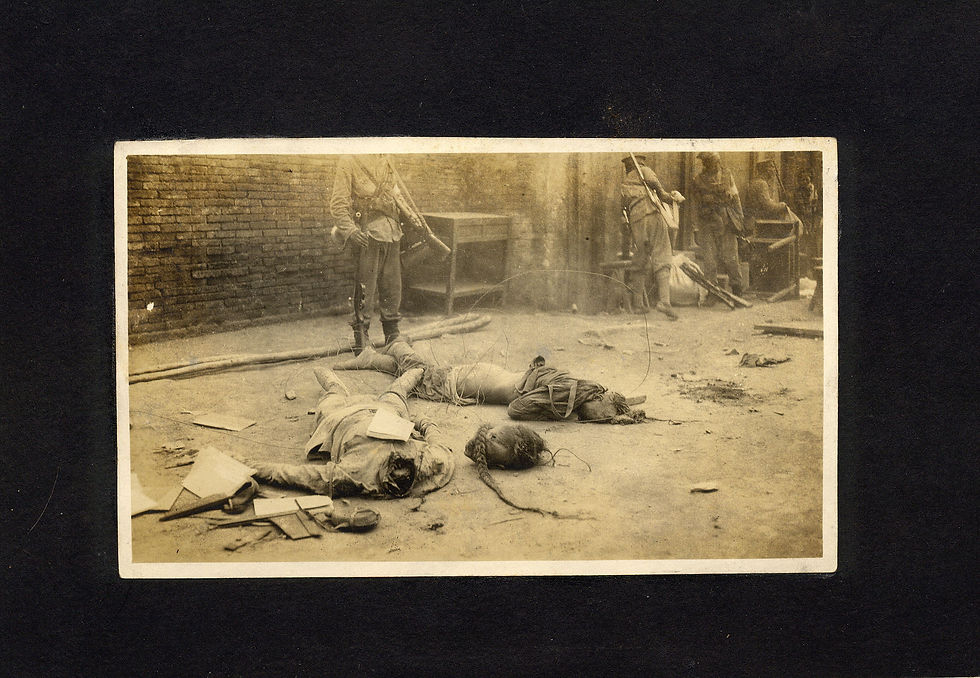

I choke on my tea as he turns the page. Grossly disfigured feet, ending in a pencil-sharp point: “Foot binding.” My breakfast nearly follows at the next few images -- two decapitated bodies lying in the street. Their heads, with long pigtails, lie a metre or so from their torsos, while uniformed Chinese police hover nonchalantly over them. “Some people who met their creator earlier than they expected,” says Larry laconically. “If you get away with anything it’s fine. But if you get caught you have to expect the penalty.”

Thora, who has been eavesdropping from the kitchen nearby, butts in: “It’s good that you’re speaking to Larry – he’s remembering things he’s never talked about.” Quite something given they’ve been married since 1948.

“No,” says Larry. “I had a pretty dull life, really."

POSTSCRIPT: Larry insisted I take his photo albums after we finished our chat. I said it was not urgent because I still had years of writing and research to go. But he insisted, packing his valuable albums into a shopping bag for me, and ushering me out the door. Just a couple of nights later their home burned to the ground, completely razed, leaving he and Thora with nothing but their underwear. I was so pleased to be able to hand them back their bag of memories -- all they had left in the world now -- once they'd moved into a new house. Some things are just meant to. Please share this blog with anyone with an interest in Old China or the Far East, thanks.

--

This blog is an edited extract from 'Tales from the Tiger's Den: An Oral History of Foreigners in the Far East 1920-2020' by Stuart Lloyd, which covers 21 foreigners, colonials, and expats in various parts of Asia in that turbulent time frame. Now available in paperback and ebook.

#OldShanghai #AmyJohnson #1931ChinaFlood #ShanghaiHistory #JazzAgeShanghai #RoaringTwentiesChina #Shanghai1920s #Shanghai1930s #TreatyPortShanghai #ColonialShanghai #ExpatLifeShanghai #ForeignConcessions #ShanghaiInternationalSettlement #ShanghaiExpatHistory #EastMeetsWest #CulturalCrossroads #WomenInAviation #AviationHistory #SoloFlight #AviationPioneer #DaredevilPilot #FlightToShanghai #YangtzeFlood #ShanghaiFloods #ChinaDisasterHistory #YangtzeRiverFlood #GreatChinaFlood #HistoryUncovered #LostWorlds #TwentiethCenturyHistory #BetweenTheWars #GlobalHistory #HerStory

Comments