How Singapore lost the war long before the first shots were fired.

- Stu Lloyd

- Sep 19, 2025

- 9 min read

You've probably heard about Britain sending out an under-cooked fleet to the Far East as a show of great force and hope to the local populations of Singapore and Malaya. And how that all went horribly wrong on the day. But strategically, Britain was outgunned by Japan long before that, which led to this ships/big guns vs planes/torpedoes showdown off the coast of Malaya in 1941. This backstory fascinates me ...

Way back in 1904 Admiral Togo (not to be confused with Tojo) put on a master-class exhibition on the use of torpedoes against the Russian fleet at Port Arthur. Ironically, those torpedoes were designed and developed by a British engineer, Robert Whitehead, who added the crucial self-propelling locomotive component. The mighty Russian fleet was scuttled in one of the most famous and improbably maritime victories ever.

Astute Japanese observers knew this was the weapon to tip naval power in their favour, because they were limited by treaty at the time by the size and quantity of warships they could build.

So in 1928 they set about a tireless five-year program to perfect a fully oxygen-powered torpedo. The result was the type 95 MK11. It could travel at a speed of 49 knots with a 1210 pound warhead and could be dropped from 5760 yards away with accuracy. It was a game-changer.

But of course it still needed a deadly mode of delivery, and this is where the Mitsubishi engineers really stepped up.

Through various experiments, iterations and prototypes, they arrived at two key models.

The Mitsubishi G3M Rikko Type 96 was a twin-engined medium bomber, stripped back with only a few light machine guns for defence, and no defensive armour at all. In 1936, its unprecedented combination of speed of 240 mph and range of around 1400 miles made it lethal. These became nicknamed “Nells”.

The Mitsubishi G4M was similarly a twin-engined land-based bomber, capable of reaching 300 mph per hour. These became known as “Bettys”.

These planes were capable of carrying bombs of up to 800kg or Type 91 torpedoes with warheads of up to 205kg. But the important performance specification was that they could deliver their loads at full throttle from as high as 1000 yards in the air.

In the summer of 1941 Rear Admiral Matsunaga Sadaichi’s 22nd Air Flotilla had been carrying out intensive sea-attack training from fields in South Formosa (Taiwan).

Aircrews of both carrier-based and land-based crews were highly trained, experienced and skillful. In training manoeuvres they boasted a ‘hit’ rate on battleships three out of every four times (74%), and even in real combat situations this was estimated at 25%.

But now they would need to step it up a level against the British around Malaya and the South China Sea.

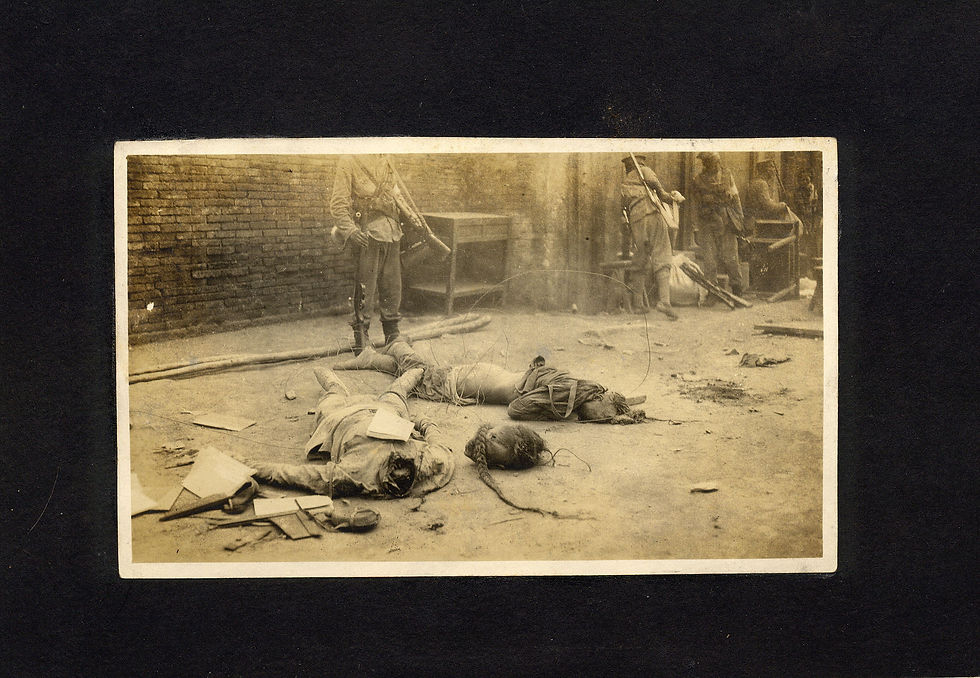

Air support for Yamashita’s 25th Army -- tasked with taking Malaya -- fell to the crack 3rd Division, comprising 350 planes. The 22nd Air Flotilla had seen combat service in China already, especially around Chengdu and Qongqing, with much success against Chinese shipping too.

The 22nd was divided into three Corps: Mihoro with 48 Nells, Genzan with 48 Nells, and Kanoya with 48 Bettys.

In October 1941, the Mihoro and Genzan Corps flew south via Hainan to IndoChina, using the Thudaumot and Soctrang fields around Saigon, where the flotilla was HQ’d.

So Japan had strategically gone big on offensive air warfare.

But they’d also built up massive naval power to facilitate such strike power. Yamamoto had nine aircraft carriers under his command in 1941, more than any other country.

STICKING TO THEIR GUNS

Battleships are a grand statement showpiece, and were seen as invincible by many in Whitehall, where many of the old guard in their stuffed armchairs believed that Britannia ruled the waves, still, surely.

But even US Navy capital ships like the Saratoga and Lexington made them look outmoded. The Royal Navy took the disposition that airplanes were a defensive auxiliary for their big ships and big guns, despite an increasing vocal lobby pushing for the strike power of torpedoes and torpedo bombers.

Commander Russell Grenfell noted that in the two decades since 1918 aircraft operating ranges had increased considerably: “The point seems to have been reached where fleets cannot be kept clear of shore-based aircraft,” he said.

Captain BH Lidell Hart, the Times military correspondent, sided with Grenfell. What was important, he argued, is that the very threat of destruction from the air – whether or not a bomb could actually sink a battleship – nullified the battleship’s strategic role.

But “Big Guns” was the dominant school of thought. And if big guns are good, then bigger guns must be even better.

AH Pollen was an author, lawyer and pioneer in naval range-finding and gunnery. “No weapon or device can supplant the gun,” he said in a quote that was oft requoted at the highest levels of The Admiralty. “The belief, carefully fostered in the public mind, that huge bombs will rain down on battleships is childish.”

So in 1936, after a 14-year hiatus by Britain of building battleships, suddenly it was full steam ahead again. Soon five King George-V Class 35,000 tonners were on the skids. But their designs put a premium on matching the fighting power of other ships.

HMS Prince of Wales was one of these KGV class vessels laid down at Birkenhead in January 1937.

Churchill later stated that, “A KGV class battleship exercises a vague general fear and menaces all points at once. It appears and disappears causing immediate reactions and perturbations on the other side.”

Vindication was gained by those who voted for this course in May 1941 when the Prince of Wales famously chased down the Bismarck and got in three strategically important disabling shots, which slowed it and enabled its later destruction by others. Captain John Leach was injured and spent his leave in hospital while his ship was repaired and upgraded.

Now she was bristling with short-range and long-range weapons, as well as guns against high-level and low-level air attacks, even if her main 14” guns were the smallest main weapons fitted since 1912. And if that wasn’t enough, six inches of steel plating on her decks, and an anti-torpedo bulge on her bow, promised to make her unsinkable.

Unsinkable, in the same way that Singapore was impregnable.

But the crew was not yet fully “worked up” meaning they were not yet familiar with the nuances of the new machinery and weaponry. In any case they were selected to take Churchill to his Atlantic Conference with Roosevelt in Newfoundland on 14 August 1941.

**

HMS Repulse was born of an entirely different mindset in January 1915 at the John Brown and Co shipyards on the Clyde River. The idea was to create a ship that could deal with the contemporary stalemate in the Baltic. The winning strategy to break the deadlock was deemed to be an escort ship with light draught but the heaviest guns possible, and a very high speed, to play mother-duck to an amphibious invasion force. So two ships were delivered to this specification – 6 x 15-inch guns. Tick. 32 knots. Tick. And the thinnest possible armour-plating. Tick. Although she was built in near-record time of 18 months, by the time she sailed, three of her close sisters had been sunk by the Germans, and the battle in Jutland she was originally designed for was over.

However, concessions were made to the new torpedo threat by having a 14’ wide buffer zone bulge of oil and water compartments running the length of the vessel. Post-WW1 she was refitted with “an inch or two” of hardened steel on her decks and four anti-aircraft guns. Deemed enough to be a contender in the ‘Air Age’.

For two years from 1934 she was docked at Portsmouth with further strengthening work done against possible effects from torpedos and bombs. She became known rather disparagingly as ‘HMS Repair’. She now had six new anti-aircraft weapons fitted – 2 x four-barrel two pounders, and was supposed to get 4 x eight-barrel Pom-Poms but only two were available because of the construction frenzy.

“On 3 January 1939 an era began in my life, which I still hold close to my heart, the memories will never fade of the wonderful times I had onboard this ship,” said Boy Seaman Ian Hay. “The setting where Repulse was berthed couldn’t have been more fitting, moored alongside Nelson’s Victory, a proud sign of continuing British sea power. The only trouble was, the whole ship looked like it had just been salvaged from the depths of the ocean. I had a job to walk on the decks, in fact in certain places on the ship the deck wasn’t visible because of coils of electrical cable, riveting and welding equipment.”

In August 1941, Repulse was earmarked for service in the Far East. She finally had an additional Pom-Pom fitted, but with the urgency building, plans for modern anti-aircraft radar and many more high-angle guns had to be thrown out of the porthole.

1941 was proving to be the year of big distractions for Churchill. The Barham, Ark Royal and Hood had been sunk in the European war to date, and merchant marine losses were touching the million-ton level thanks to U-Boat activity. The war in the Middle East was delicately poised. The Russians needed to be supplied for their front. Apart from the whole European theatre, of course. Japan, Malaya, all those other places? A damned nuisance really. “The whole Japanese menace lay in a sinister twilight compared with our other needs,” said Winston Churchill.

Japan was gratified and vindicated in its strategic course by watching the results of the war so far: of nine capital ships sunk, only one third had been at the hands of the big guns of another ship. All others had been sunk by torpedo. It seemed they had backed the right horse.

“Narrowly we scanned our resources,” said Churchill, before deciding that capital ships were the answer for the Far East. He himself was a product of that great battleship era. He particularly loved their deterrent appeal. Admiralty championed long and hard against such a token fleet of Repulse, Wales, and the new carrier Indomitable but the decision was taken on 20 October 1941. Sir Dudley Pound of the Admiralty reluctantly compromised on two conditions: that the Prince of Wales be accompanied by an aircraft carrier, and that her destination be reviewed en route according to prevailing conditions.

Commander in Chief of Eastern Fleet was Acting Admiral Sir Tom ‘Tom Thumb’ Phillips. He was once very socially close with Churchill but less so now after a disagreement over the strategy of retaliatory land bombing. So his appointment was a bit of a surprise, especially as he’d not been to sea for years and never commanded a battleship. But his determination was as unquestionable as his humour was absent.

At 53 he had a ton of experience under his belt, serving in the Far East and Mediterranean, and becoming a captain in the closing year of WW1. He, too, was a “big gun” man and didn’t highly regard the bomber for its strategic or tactical worth.

On 24 October, Tom took a train to Glasgow, then boarded the Wales and hoisted his flag. They sailed for Cape Town. Then came the unwelcome news that the carrier Indomitable was accidentally damaged in the West Indies and held up for repairs. The Wales set sail, and arrived at Colombo for her rendezvous with Repulse on 28 November. The word was now out – Britain had a Far East Fleet. But still no replacement for the Indomitable had been found.

Z Force – as the flotilla was code-named -- consisted of the battleship flagship Prince of Wales, Repulse a battle cruiser, and four supporting destroyers, Electra, Express, Tenedos, and an Australian ship HMAS Vampire.

Phillips took a flying boat ahead to Singapore to try and rustle up the rest of a decent flotilla, because now two destroyers from the Mediterranean were also no-shows.

**

Watching them sail down the Straits of Malacca were Father Brendan Rogers and his fellow Aussies from the 2/10th. “We saw the Repulse and Prince of Wales come down the Straits. We thought, ‘We’re right now, the Navy’s here’.” You can bet the Japanese were watching Z Force with great interest, too.

Two key strategic decisions had set up this death match off Malaya: first, the Japanese preponderance for air power as a first strike tactic, thanks to Yamamoto’s vociferous lobbying of the Japanese Navy Department, and second, the Whitehall decision to try and intimidate and deter with two battleships instead of sending more modern aircraft, artillery, or even tanks.

Intense training for their 22nd Air Flotilla continued until late November when news came of the Colombo flotilla, which enticingly included what was believed to be Britain’s most modern battleship. Matsunaga called forward three more squadrons, the 27 Bettys of Kanoya Corp. Now a total of 123 of the world’s leading naval attack aircraft were poised to strike from Vietnam.

Phillips estimated he would be safe from torpedo bombers if he operated outside of 200 miles from the Japanese’ new bases in IndoChina. This political change of allegiance by the French had brought the front-line threat 1500 miles closer overnight, negating all the strategic planning and thinking regarding Malaya’s airfields which were dotted around Kuantan, Kota Bahru, Alor Star, and so on.

Tennant to Pulford: “If we need it, are you going to be able to provide us with air cover?”

“Yes, of course.”

**

At dawn on 4 December Lt Gen Yamashita of the IJA 25th Army watched expectantly through his heavy-lidded eyes as 27 troop ships slid out of Hainan, destination Malaya. He carried the hopes of 100,000,000 Japanese on his back ...

This is an edited extract from Stuart Lloyd's short book 'The Depths of December: The Sinking of HMS Repulse, HMS Prince of Wales ... and the British Empire'. Available now in ebook and audiobook.

Comments